He began a poor sharecropper in the south playing acoustic blues until heading north, going electric, & taking the history of the music with him.

Others that did it along side of him were Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf, & John Lee Hooker--his only real rivals for the king of the modern electric blues.

But as his name implied, it was B.B. who would be King. He wasn't particularly sexy like Muddy Waters, raw like Howlin' Wolf, or cool like John Lee Hooker, but maybe that was point. He simply took all of those traits & melded them together into something that was greater than the sum of its parts--a platonic ideal of the blues, defined by call-&-response singing & playing, clever lyrics, & a passion that could be felt coming straight through the record.

Perhaps because he was younger, perhaps because he lived longer, perhaps because he was simply more mainstream, B.B. King outstripped the success of his contemporaries & owned the music as its living embodiment, in a way that James Brown did for soul & Johnny Cash did for country. Which is to say that he wasn't necessarily the greatest or most influential performer in his field, he just kept on going through a key period of time & let the genre come to him.

God knows he worked hard for it.

In The New York Times' obituary of King, they report that he played no less than 342 one-night stands in 1956 alone. Think about that for a minute. That means the year that Elvis broke rock music through to the mainstream & Eisenhower won a second a term in a landslide, B.B. King had exactly 24 days off (1956 was a leap-year), on average one every other week.

Less than a decade later, in 1965, when he recorded his signature LP, Live At The Regal, he was already billing himself as "The King Of The Blues" with a straight face. The album, which has since won virtually every accolade an album can,

from being inducted to The National Recording Registry to The Grammy

Hall Of Fame, bears the title out. B.B. King--& as some argue, the blues itself--is in top form, turning love into loss & sadness into irony.

Hear the way he opens with "Every Day I Have The Blues" but turns it into a badge of honor instead of a lament. Listen to the way he sings about the way in which the title figure in "Sweet Little Angel" spreads her wings & marvel at the simplicity with which he unites the sacred & the secular. & check out the album's most famous moment, in the breakdown of "How Blue Can You Get?" where he sings, "I gave you seven children & now you want to give them back!" & the way the audience responds; the only thing that matches it in American music are James Brown drawing out "Lost Someone" on his Live At The Apollo & Johnny Cash singing about how he shot a man "just to watch him die" in "Folsom Prison Blues" on Live At Folsom Prison.

Hear the way he opens with "Every Day I Have The Blues" but turns it into a badge of honor instead of a lament. Listen to the way he sings about the way in which the title figure in "Sweet Little Angel" spreads her wings & marvel at the simplicity with which he unites the sacred & the secular. & check out the album's most famous moment, in the breakdown of "How Blue Can You Get?" where he sings, "I gave you seven children & now you want to give them back!" & the way the audience responds; the only thing that matches it in American music are James Brown drawing out "Lost Someone" on his Live At The Apollo & Johnny Cash singing about how he shot a man "just to watch him die" in "Folsom Prison Blues" on Live At Folsom Prison.

It is on one hand a public performance, but on the other a private confession. Now, maybe James Brown did lose someone & Johnny Cash at some point felt like shooting a man just to watch him die, but B.B. King, who by his own account fathered some 15 children by 15 different women, might have actually felt at some point like giving them back. It is perhaps this kernel of truth that gives the performance its wrenching bite, & it is what we respond to a half-century after its release.

* * *

Also unlike James Brown & Johnny Cash, I was fortunate enough to see B.B. King play live.

It was 1996 in Austin, Texas, soon after he released his autobiography Blues All Around Me. I read the first part of the book out of obligation of the concert coming up--I always found that co-author David Ritz, who did such a great job on the Ray Charles & Marvin Gaye autobiographies, did a bit of an overwrite on his part when trying to capture King's voice--& listened to Live At Regal & the few other B.B. King recordings I had around. When it came to the classic blues, I was always more interested in the old, scratchy Robert Johnson & Charley Patton stuff; when it came to the electric blues Howlin' Wolf was my man.

All of which is to say that B.B. King was far from my favorite artists.

But his concert was one of the best I've ever seen.

I've seen lots of great shows--from the likes of Bob Dylan, Paul McCartney, & Eric Clapton on down through Elliott Smith, The Pixies, & Guided By Voices--but B.B. King had a power that could only be compared to Chuck Berry & Jerry Lee Lewis. There's something about that pre-television generation who were doing it before rock was born & continued doing it once it had splintered into a million pieces, that gave them a power that not even the finest Bob Dylan concert could begin touch. I suspect the same would've been true had I seen James Brown or Johnny Cash; I know the same would've been true had I seen Elvis.

But B.B. King. In some ways, his concert was the best because, compared to Chuck Berry & Jerry Lee Lewis, he was the biggest. He came out in a silver-sequined jacket suit that made him look like a disco ball, beaming as he opened with "Every Day I Have The Blues." He had Lucille, his signature black Gibson guitar, & made his weird "lemon" faces as he jammed, over-fluttering his fingers with each touch of vibrato so that his hand looked like a mad butterfly.

He didn't so much sing & play as much as he did hold court. The audience was enraptured from the first moment he stepped on stage & the band--complete with a rhythm section & horn section--followed his every move, knowing when to turn things up for a rocker & shift it back down for a ballad or solo.

It is the only concert I had ever seen where the music literally did not stop--the backing musicians simply keep the 12-bar blues going quietly while he spoke between the songs. Some people don't like the blues--& in turn, B.B. King--because they think every song sounds the same. B.B. King's concert turned this notion on its head, literally playing the entire set like it was a single song. In so doing, he both proved this criticism of blues music while pulling the rug out from under it, showing how so many different moods & textures could emerge from the same primordial blues swamp.

* * *

As I mentioned earlier, I saw B.B. King in the mid-'90s, when MTV's Unplugged show had redefined music was performed--as exemplified by artists as diverse as Eric Clapton & Nirvana. Everyone who was a serious artist or band seemed to want to make an "unplugged" album--many of whom did so on the official program (Rod Stewart & Tony Bennett) & many others who did so on their own (think The Rolling Stones' Stripped, if you can remember that).

B.B. King did a similar thing at the middle of his show. At one point, the horns & extraneous musicians strutted off to the sides, while a core blues combo remained, with B.B. King doing what Clapton & Kurt Cobain did on MTV: He sat in a chair. King played a more intimate, down-home blues that sounded closer to the small bands that Muddy Waters first recorded with in Chicago than his own flashy stage show. It was all so well choreographed & performed, it made me almost forget that he was probably doing this at least in part to mask his diabetes had made him too weak to stand for an entire performance. But I digress.

At any rate, this smaller, more focused blues playing was the blues that I liked to hear, with less going on & more focus on the lyrics and the interaction between the instruments. It wasn't an "Unplugged" show per se--B.B. still held onto his electric Lucille--but it had all the trappings of one. After all, Elvis's "sit-down" show of his "'68 Comeback Special," which inspired MTV Unplugged in the first place, featured the King (this time of rock) playing an electric Gibson.

With the mood & the playing more down-home, B.B. King spun some good stories. Turns out he is as good of a storyteller as he is a performer (as if the two could be separated) & with his actual hard life--which is to say, the fact that he had grown up poor on a sharecropping farm--it made everything feel more real, earned, & special.

At one point, he talked about the fish-fry parties that people threw to make rent money, how everyone would come out with bootleg liquor, how the blues combos would play for hours on end, how the people would dance and dance, how this late-night celebrations were such a welcome escape from their early morning farm work; "& then as the night kept wearing on," B.B. King said, "Until the time that the sun was coming up for a new work day, & we'd all say--"

THE THRILL IS GONE!

With those words, the stage exploded with excitement as the horn players & extra musicians reappeared on cue, & B.B. King stood up from the chair to perform with his full band once again. Before anyone could catch their breath, B.B. King was singing "The Thrill Is Gone," his signature biggest hit & the first song most people know him by.

For someone whose music was so timeless, "The Thrill Is Gone" sounds very much like the time in which it was recorded, in a late-'60s haze where rock had conquered blues & funk was threatening to conquer rock. It is a slow blues, with keyboard & strings, but is such a good performance--such a good idea--that it cuts through its surroundings.

The thrill is gone, the thrill has gone away

The thrill has gone, baby, he thrill has gone away

You know you done me wrong baby

& you'll be sorry someday

What more has the blues ever tried to say? There is simplicity to this song, a logic that maintains its strength. Taken altogether, it is little wonder that this is the quintessential blues song of the quintessential blues performer.

Even as I watched B.B. King live singing this in a manner that was entirely rehearsed, I knew I was experiencing something very special--& very real. For, despite what B.B. King was singing to me at that moment, the thrill was here.

He cut records for Sam Phillips at Sun Records three years before Elvis Presley walked through the door.

He had a #1 R&B single, "3 O'Clock Blues," in February 1952, before contemporaries like Fats Domino, Ray Charles, Little Richard, & James Brown had done the same.

He would have an additional 3 #1 R&B records--"You Know I Love You," "Please Love Me," & "You Upset Me Baby"--all before Bill Haley & His Comets scored rock's first #1 pop hit, "Rock Around The Clock."

He kept playing one-night stands through Elvis, through Beatlemania, through Dylan plugging in, & Jimi Hendrix setting his guitar on fire; if the resulting document of this period, 1965's Live At Regal, is any indication, on a good night he could at the very least meet any of these artists on his own terms.

He played Bill Graham's Fillmore West in 1968 to a full house of long-haired white hippies, & found his music embraced by a new audience.

He released his signature hit, "The Thrill Is Gone," late in 1969, capping rock's finest year that included Elvis's From Elvis In Memphis, The Beatles' Abbey Road, & The Rolling Stones's Let It Bleed--not to mention Hendrix at Woodstock, Bob Dylan at The Isle Of Wight, & The Stones at Altamont. It would become his biggest pop hit (#15 on the pop charts & #3 on the R&B charts) & score him his first Grammy Award (for 1971's Best Male R&B Vocal Performance). When David Cassidy was trying to establish his cred in the early '70s, he cited "The Thrill Is Gone" as his favorite song.

In 1977, he straddled both sides of the cultural spectrum by appearing as himself on an episode of Sandford & Son, & later receiving an honorary doctorate of music from Yale University.

In 1980, he was among the first 20 inductees into the Blues Hall Of Fame, along with the likes of Charley Patton, Son House, Robert Johnson, Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf, Willie Dixon, & John Lee Hooker.

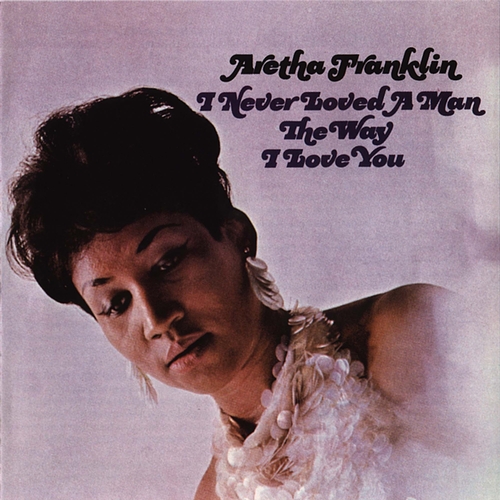

In 1987, he was among the second set of inductees into the Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame, along with the likes of Muddy Waters, Big Joe Turner, Bo Diddley, Aretha Franklin, & Marvin Gaye.

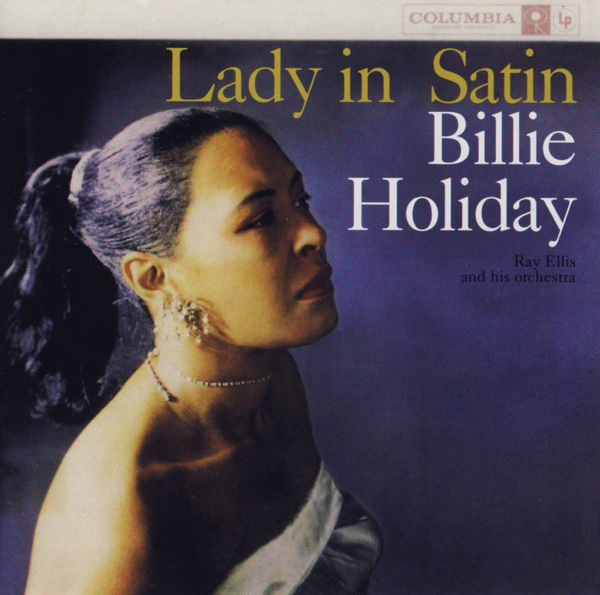

That same year he would receive a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award, making him the first blues musician to receive the honor. Other recipients that year included Billie Holiday & Hank Williams.

The following year, he recorded the hit "When Love Comes To Town" with U2 at Sun Records for their album Rattle & Hum; it was his first single to make the US rock charts (#2) & the UK pop charts (#6).

In 1990, he received The National Medal Of The Arts from President George H.W. Bush; in 2006, he received The Presidential Medal Of Freedom from President George W. Bush.

& in 2012, he was among the performers at "In Performance At The White House: Red White & Blues" where he jammed on "Sweet Home Chicago" with President Barack Obama.

I am loathe to close.

The thrill is gone, the thrill has gone away

The thrill has gone, baby, he thrill has gone away

You know you done me wrong baby

& you'll be sorry someday

What more has the blues ever tried to say? There is simplicity to this song, a logic that maintains its strength. Taken altogether, it is little wonder that this is the quintessential blues song of the quintessential blues performer.

Even as I watched B.B. King live singing this in a manner that was entirely rehearsed, I knew I was experiencing something very special--& very real. For, despite what B.B. King was singing to me at that moment, the thrill was here.

* * *

It's hard to believe that B.B. King is gone because he's always been here, a cultural institution, an epoch upon himself.

He cut records for Sam Phillips at Sun Records three years before Elvis Presley walked through the door.

He had a #1 R&B single, "3 O'Clock Blues," in February 1952, before contemporaries like Fats Domino, Ray Charles, Little Richard, & James Brown had done the same.

He would have an additional 3 #1 R&B records--"You Know I Love You," "Please Love Me," & "You Upset Me Baby"--all before Bill Haley & His Comets scored rock's first #1 pop hit, "Rock Around The Clock."

He kept playing one-night stands through Elvis, through Beatlemania, through Dylan plugging in, & Jimi Hendrix setting his guitar on fire; if the resulting document of this period, 1965's Live At Regal, is any indication, on a good night he could at the very least meet any of these artists on his own terms.

He played Bill Graham's Fillmore West in 1968 to a full house of long-haired white hippies, & found his music embraced by a new audience.

He released his signature hit, "The Thrill Is Gone," late in 1969, capping rock's finest year that included Elvis's From Elvis In Memphis, The Beatles' Abbey Road, & The Rolling Stones's Let It Bleed--not to mention Hendrix at Woodstock, Bob Dylan at The Isle Of Wight, & The Stones at Altamont. It would become his biggest pop hit (#15 on the pop charts & #3 on the R&B charts) & score him his first Grammy Award (for 1971's Best Male R&B Vocal Performance). When David Cassidy was trying to establish his cred in the early '70s, he cited "The Thrill Is Gone" as his favorite song.

In 1977, he straddled both sides of the cultural spectrum by appearing as himself on an episode of Sandford & Son, & later receiving an honorary doctorate of music from Yale University.

In 1980, he was among the first 20 inductees into the Blues Hall Of Fame, along with the likes of Charley Patton, Son House, Robert Johnson, Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf, Willie Dixon, & John Lee Hooker.

In 1987, he was among the second set of inductees into the Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame, along with the likes of Muddy Waters, Big Joe Turner, Bo Diddley, Aretha Franklin, & Marvin Gaye.

That same year he would receive a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award, making him the first blues musician to receive the honor. Other recipients that year included Billie Holiday & Hank Williams.

The following year, he recorded the hit "When Love Comes To Town" with U2 at Sun Records for their album Rattle & Hum; it was his first single to make the US rock charts (#2) & the UK pop charts (#6).

In 1990, he received The National Medal Of The Arts from President George H.W. Bush; in 2006, he received The Presidential Medal Of Freedom from President George W. Bush.

& in 2012, he was among the performers at "In Performance At The White House: Red White & Blues" where he jammed on "Sweet Home Chicago" with President Barack Obama.

* * *

There was still so much I wanted to say--how B.B. King's first Top 40 hit, "Rock Me Baby," occurred in 1964 & would be covered by Otis Redding & Jimi Hendrix by the decade's end; how he sang about his brother going to Korea in 1960's "Sweet Sixteen" & would later change the line to be about coming back from Vietnam the following decade; how over time his records became more commercial & pop-oriented, with strings providing call-&-response lines along with his guitar; how in a recording from 1979, he tells the Queen Of England to never look down.

How some of his best song titles played like hard-earned truths of sage advice: "Paying The Cost To Be The Boss." "Never Make A Move Too Soon." "Help The Poor."

How in 1971, he sang what is perhaps the greatest blues lyric of them all:

Nobody loves me but my mother--

& she could be jivin' too.

The King is dead. Long live the King.